|

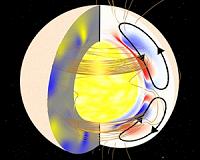

Paris (AFP) March 3, 2011 Space scientists on Thursday said they could explain why spots disappeared off the face of the Sun for two years, a mystery that had challenged a mainstream theory about our star. The years 2008 and 2009 were marked by a near-absence of sunspots, which reflected an unusually long period of low solar activity. Astronomers were perplexed, for at that time the Sun was supposed to be building towards the climax of an 11-year cycle that has big implications for life on Earth. Sunspots are highly magnetised globs of charged particles called plasma on the solar surface. Plasma circulates on the Sun in a movement called the "Great Conveyor Belt" that bears similarities to Earth's ocean currents. The conveyor belt travels along the Sun's surface, plunges inward around the poles and then re-emerges near the equator. When sunspots start to decay, the surface currents sweep up their demagnetised remains and haul them into the bowels of the Sun where, at a depth of 300,000 kilometres (187,000 miles), their magnetic field is recharged. The remagnetised plasma then rises back up to the surface -- and the sunspot is reborn. The answer to the sunspots' absence comes in a computer model proposed by Dibyendu Nandi of the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research in Kolkata and colleagues. It looks at what happened in 2008-9, factoring in the interior of the Sun, its magnetic "dynamo," the Great Conveyor Belt and the way sunspots are magnetically recharged and recover buoyancy. "According to our model, the trouble with sunspots actually began in back in the late 1990s," co-author Andres Munoz-Jaramillo of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics said in a press release. "At that time, the conveyor belt sped up." Put simply, the Great Conveyor belt dragged decaying sunspots down to the heart of the Sun for a magnetic reboost -- but the process this time was way too fast for the sunspots to be fully reanimated. As a result, new sunspots failed to surface from the hidden production line. "The stage was set for the deepest solar minimum in a century," said Petrus Martens of the Montana State University Department of Physics. The findings, published in the British journal Nature, add important knowledge about solar mechanics, the authors hope. At the solar cycle's most active point -- a period called solar maximum -- sunspots dot the Sun's surface and the star can spew billions of tonnes of plasma that can disrupt communications and electrical grids and short-circuit satellites. During solar minima, sunspots are rare, as are the displays of anger, but it can still have a significant impact for us on Earth. The planet's outer atmosphere shrinks closer to the surface, meaning there is less drag on orbiting space junk, and the "solar wind" that blasts from the Sun weakens, meaning that more cosmic rays from interstellar space reach our planet. The latest solar cycle began in 1996 and is likely to end in mid-2013, although a solar "max" is usually preceded by a period of eruptions that can last as much as two and a half years, say experts. Last month, the strongest eruption in five years unleashed auroras in northern skies and disrupted some radio communications, but damage was limited because of a fortuitous alignment with Earth's protective magnetic field.

Share This Article With Planet Earth

Related Links Solar Science News at SpaceDaily

Researchers Crack The Mystery Of The Spotless Sun

Researchers Crack The Mystery Of The Spotless SunGreenbelt MD (SPX) Mar 03, 2011 In 2008-2009, sunspots almost completely disappeared for two years. Solar activity dropped to hundred-year lows; Earth's upper atmosphere cooled and collapsed; the sun's magnetic field weakened, allowing cosmic rays to penetrate the Solar System in record numbers. It was a big event, and solar physicists openly wondered, where have all the sunspots gone? Now they know. An answer is being p ... read more |

|

| The content herein, unless otherwise known to be public domain, are Copyright 1995-2010 - SpaceDaily. AFP and UPI Wire Stories are copyright Agence France-Presse and United Press International. ESA Portal Reports are copyright European Space Agency. All NASA sourced material is public domain. Additional copyrights may apply in whole or part to other bona fide parties. Advertising does not imply endorsement,agreement or approval of any opinions, statements or information provided by SpaceDaily on any Web page published or hosted by SpaceDaily. Privacy Statement |